If you have ever stared at your screen wondering why a variable is suddenly undefined or why your loop is printing the same number ten times, you have likely run into a scope issue.

Scope is one of the most fundamental concepts in JavaScript. It is also one of the most confusing for beginners. When you misunderstand scope, your code becomes fragile. Variables leak into places they shouldn't be, and functions break in unexpected ways. But once you master it, you gain complete control over your code’s behavior.

In this guide, we will break down exactly how JavaScript handles scope. We will move past the technical jargon and use plain English to explain where your variables live, who can see them, and how to avoid the mistakes that trip up almost every new developer.

What is Scope?

In simple terms, scope is the set of rules that determines where you can access a specific variable in your code. Think of scope like a security clearance level in a building.

If you have "Level 1" clearance (Global Scope), you can go anywhere. If you have "Level 5" clearance (Local/Block Scope), you are restricted to a specific room. If you try to access a variable that is outside your clearance level—or outside your current room—JavaScript will stop you with an error.

Scope controls the visibility and lifetime of variables. It answers two questions:

- Where can I use this variable?

- How long does this variable exist in memory?

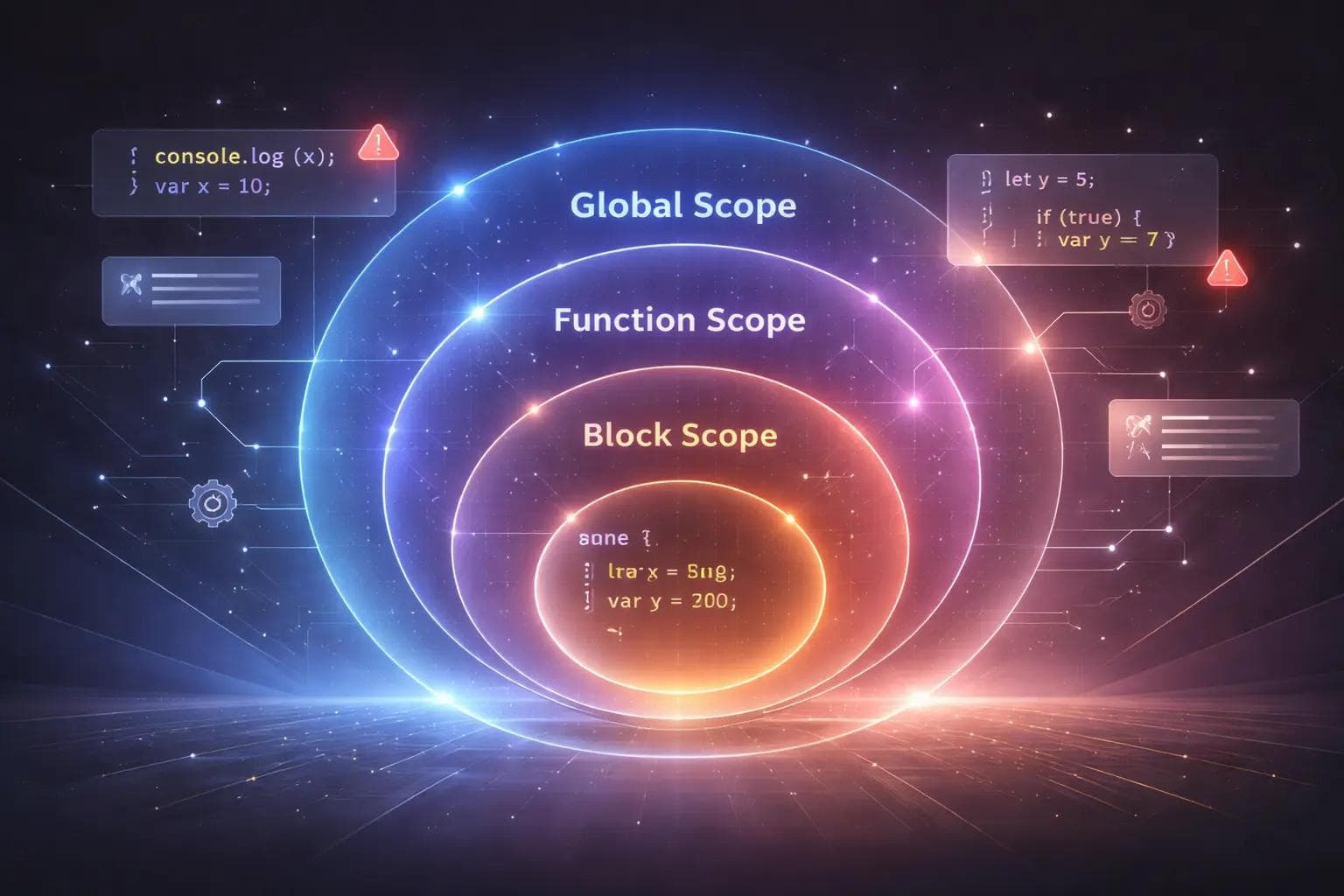

The Three Main Types of Scope

Before ES6 (the major JavaScript update in 2015), things were a bit simpler but messier. Today, modern JavaScript generally deals with three types of scope: Global, Function, and Block.

1. Global Scope

A variable is in the Global Scope if it is declared outside of any function or block. It is the default space.

Variables here are like public celebrities. Everyone knows them. Any function, block, or script in your application can read and modify a global variable.

1// This variable is in the Global Scope

2let username = "Alex";

3

4function sayHello() {

5 // We can access 'username' because it is global

6 console.log("Hello, " + username);

7}

8

9sayHello(); // Output: Hello, AlexWhy is this dangerous? While global variables seem convenient, they are a major cause of bugs. If you have a global variable named data, and a third-party library you install also uses a global variable named data, one will overwrite the other. This is called namespace pollution. Generally, you want to keep your global scope as clean as possible.

2. Function Scope

For a long time, this was the main way we created private variables. Variables declared inside a function are Function Scoped. They are only visible inside that specific function.

Think of a function like a house with tinted windows. You can see out (access global variables), but no one outside can see in (access local variables).

1function calculateScore() {

2 // This variable is Local to this function

3 let score = 100;

4 console.log(score); // This works

5}

6

7calculateScore();

8// console.log(score); // Error! score is not definedIf you try to access score outside of calculateScore, JavaScript will throw a ReferenceError. The variable simply doesn't exist outside those curly braces.

3. Block Scope (The Modern Standard)

This is where things changed with ES6. Before 2015, JavaScript variables declared with var did not respect blocks like if statements or for loops. They only respected functions.

Today, we use let and const. These keywords create Block Scope. A block is anything wrapped in curly braces { ... }.

1if (true) {

2 // This variable only exists inside this IF block

3 let secretMessage = "Hidden";

4 const pi = 3.14;

5

6 // VAR ignores block scope!

7 var leakedVariable = "I am everywhere";

8}

9

10// console.log(secretMessage); // Error: not defined

11// console.log(pi); // Error: not defined

12

13console.log(leakedVariable); // Output: "I am everywhere"This example highlights why var is largely considered obsolete for modern development. Using let and const ensures that variables created inside an if statement stay there, preventing accidental bugs.

Lexical Scope: The "Nesting Doll" Rule

You will often hear the term Lexical Scope. It sounds complex, but it just refers to the physical location of your code.

Lexical scope means that a function looks "outward" for variables. If a function is nested inside another function, the inner function has access to its own variables plus the variables of the outer function.

Think of it like a set of Russian nesting dolls:

- Inner Scope: Checks its own pockets first.

- Outer Scope: If not found, it asks its parent.

- Global Scope: If still not found, it asks the global scope.

1let outerVar = "I am global";

2

3function parentFunction() {

4 let parentVar = "I am in the parent";

5

6 function childFunction() {

7 let childVar = "I am in the child";

8

9 // The child can access all three!

10 console.log(childVar);

11 console.log(parentVar);

12 console.log(outerVar);

13 }

14

15 childFunction();

16}The reverse is strictly not true. The parent cannot see inside the child function. Scopes only look outward (or upward), never inward.

Common Beginner Mistakes

Understanding the theory is one thing; debugging it is another. Here are the most common ways beginners trip over scope, and how to fix them.

Mistake 1: The "Leaking Global" Accident

If you assign a value to a variable without declaring it (forgetting let, const, or var), JavaScript behaves strangely. In "strict mode", it throws an error. But in non-strict mode, it automatically creates a Global Variable, even if you are inside a function.

1function badPractice() {

2 // We forgot 'let' or 'const'

3 mistake = "I am accidentally global";

4}

5

6badPractice();

7console.log(mistake); // It prints! This is bad.The Fix: Always explicitly declare your variables. Better yet, use use strict"; at the top of your files to prevent this behavior entirely.

Mistake 2: The var Loop Issue

This is a classic interview question. Because var is function-scoped (not block-scoped), it behaves unexpectedly in loops, especially when asynchronous code like setTimeout is involved.

1// The Problem

2for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

3 setTimeout(function() {

4 console.log(i);

5 }, 1000);

6}

7// Expected Output: 0, 1, 2

8// Actual Output: 3, 3, 3Why did this happen? There is only one variable i shared across the entire loop. By the time the setTimeout runs (after 1 second), the loop has already finished, and i has reached the value of 3.

The Fix: Simply change var to let. let creates a new scope for every iteration of the loop.

1// The Solution

2for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

3 setTimeout(function() {

4 console.log(i);

5 }, 1000);

6}

7// Output: 0, 1, 2Mistake 3: Shadowing Variables

Shadowing happens when you declare a variable with the same name as a variable in an outer scope. The inner variable "shadows" (hides) the outer one. This isn't technically an error, but it is confusing and leads to bugs where you think you are updating a global variable, but you are actually updating a local one.

1let user = "Alice";

2

3function updateUser() {

4 // This creates a NEW local variable named 'user'

5 // It does NOT update the global 'user'

6 let user = "Bob";

7 console.log("Inside:", user); // Bob

8}

9

10updateUser();

11console.log("Outside:", user); // AliceIf you intended to update the global variable, you should not have used let inside the function. You should have just written user = "Bob.

Mistake 4: Hoisting Confusion

Hoisting is JavaScript's behavior of moving declarations to the top of the current scope during the compilation phase.

- var: Hoisted and initialized with undefined. You can access it before the line where you wrote it, but it will be undefined.

- let and const: Hoisted but uninitialized. If you try to access them before the declaration line, you get a "Temporal Dead Zone" (TDZ) reference error.

1console.log(myVar); // Output: undefined (Not an error!)

2var myVar = 5;

3

4console.log(myLet); // Error: Cannot access 'myLet' before initialization

5let myLet = 10;Beginners often rely on var hoisting without realizing it, leading to code that is hard to read. The best practice is to always declare variables at the top of their scope to make the flow logical.

Closures: Scope’s Superpower

You cannot discuss scope without mentioning Closures. A closure is what happens when a function "remembers" the scope in which it was created, even after that scope is gone.

This is a direct result of Lexical Scope.

1function createCounter() {

2 let count = 0;

3

4 return function() {

5 count++;

6 return count;

7 };

8}

9

10const myCounter = createCounter();

11

12console.log(myCounter()); // 1

13console.log(myCounter()); // 2

14console.log(myCounter()); // 3Even though createCounter has finished running, the inner function maintains a link to count. This allows for powerful patterns like private variables and data encapsulation, which are crucial in advanced JavaScript development.

Best Practices for Managing Scope

To keep your code clean and bug-free, follow these simple rules:

1. Default to const

Always start by declaring variables with const. This prevents you from accidentally reassigning values that shouldn't change. If you know a variable needs to change (like a counter), use let.

2. Avoid var Completely

Unless you are working on a very old legacy codebase, there is almost no reason to use var. It creates confusion with hoisting and lacks block scope. Stick to let and const.

3. Keep Scope Small

Declare variables as close as possible to where they are used. Do not declare all your variables at the top of the file if they are only used inside a specific function or if block. The tighter the scope, the fewer chances for collisions.

4. Name Variables distinctly

Avoid generic names like data or item in the global scope. If you shadow a variable, make sure it is intentional and that the naming makes it clear why (e.g., passing user into a function that already has access to a global user).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can I access a variable defined in an if block outside of that block? A: If you used var, yes. If you used let or const (which you should), then no. The variable is destroyed once the if block finishes execution.

Q: What is the "Temporal Dead Zone"? A: This is the time between the start of a scope and the point where a variable is declared. If you try to access a let or const variable in this zone, JavaScript throws an error. It protects you from using variables before they exist.

Q: Is global scope always bad? A: Not always. Constants (like configuration URLs or color codes) are fine in the global scope. However, for application state (like "is the user logged in?"), it is better to use state management or module imports rather than raw global variables.

Q: Does scope affect performance? A: Technically, yes. Searching for a variable in the local scope is faster than searching up the chain to the global scope. However, in modern browsers, this difference is negligible. You should optimize for code readability over micro-performance gains.

Conclusion

Scope is the invisible skeleton of your JavaScript code. It dictates where data lives and how different parts of your application talk to each other.

To summarize the key takeaways:

- Global Scope is for data everyone needs to see (use sparingly).

- Function Scope locks variables inside a function.

- Block Scope (let/const) locks variables inside curly braces and is the modern standard.

- Lexical Scope means inner functions can access outer variables, but not vice-versa.

By understanding these rules, you move from "guessing" why your code works to "knowing" exactly how it executes. The next time you see an undefined error, you won't panic—you will check your scope.

About the Author

Suraj - Writer Dock

Passionate writer and developer sharing insights on the latest tech trends. loves building clean, accessible web applications.